Last weekend, I played a concert with the incredible vocalist Jackie Evancho. It was just the two of us on stage, piano and voice. When playing with a band or, as is usually the case with Jackie, with a string quartet or orchestra, things are fairly set in stone, and deviating from the written music is challenging. So I always love these kinds of duo performances because they really allow for freedom in accompaniment and harmonic exploration.

For instance, I had some fun taking creative liberties during the song “Over the Rainbow.” Instead of playing a regular turnaround (C – Am7 – Dm7 – G7), I found myself squeezing in so-called Coltrane changes (C – Eb7 – Abmaj – B7 – Emaj – G7). Watch below:

This was an impulsive moment, and had it been performed with a band, I probably wouldn’t have been able to do it.

What are Coltrane changes?

When I put a poll out on social media asking if people ever use these Coltrane changes in a turnaround, most people responded with “What are Coltrane changes?”, so I decided to write this blog post and show you.

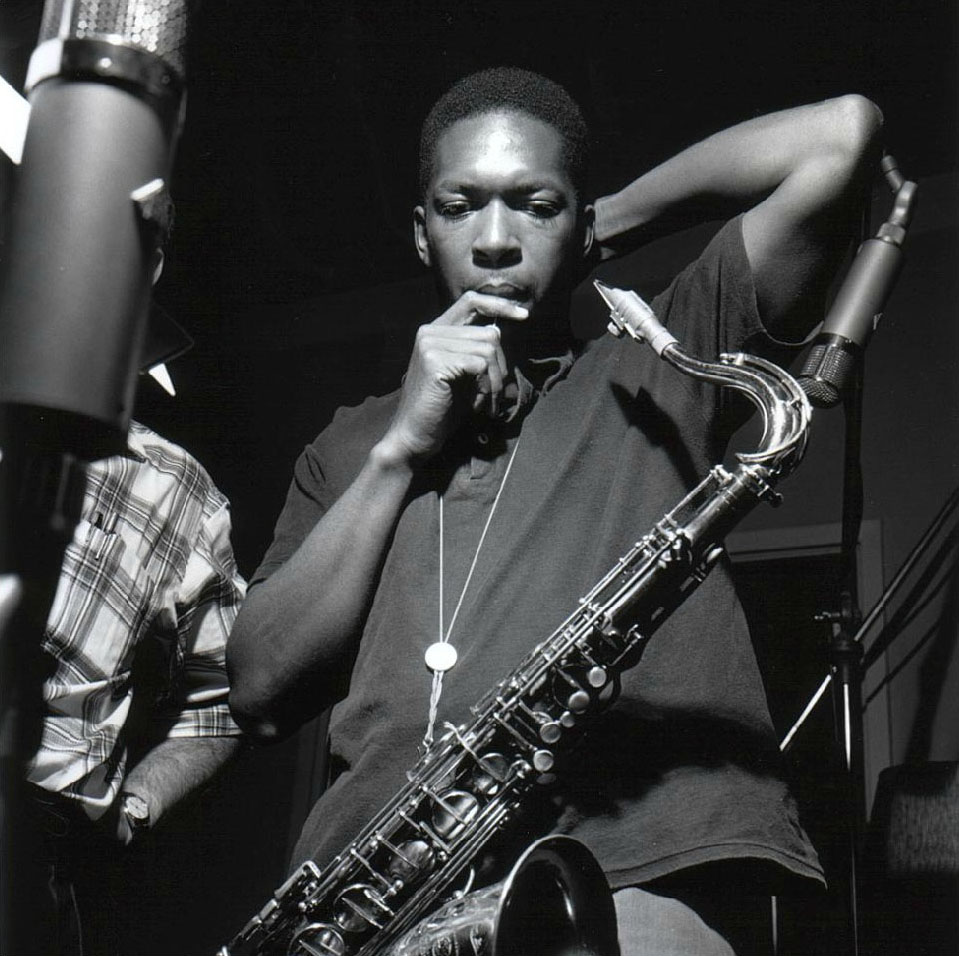

John Coltrane is generally considered to be the most famous and innovative modern jazz saxophonist who ever lived. Some of his compositions have become hallmarks of jazz, and are often incredibly hard to play and improvise over. This has led tunes such as “Giant Steps,” “Countdown,” and “26-2” to become sort of litmus tests of jazz proficiency. Jazz students tend to spend countless hours in practice rooms, working diligently to master their intricate harmonies and rapid chord changes.

These Coltrane compositions are known for using a specific harmonic structure based on modulating in major thirds. This was a departure from traditional jazz harmony, although earlier examples of these kinds of progressions can be found in other composers. These chord progressions became known as Coltrane changes. In this blog post, I’ll show you what they are and how you can use them in your own playing.

Giant Steps

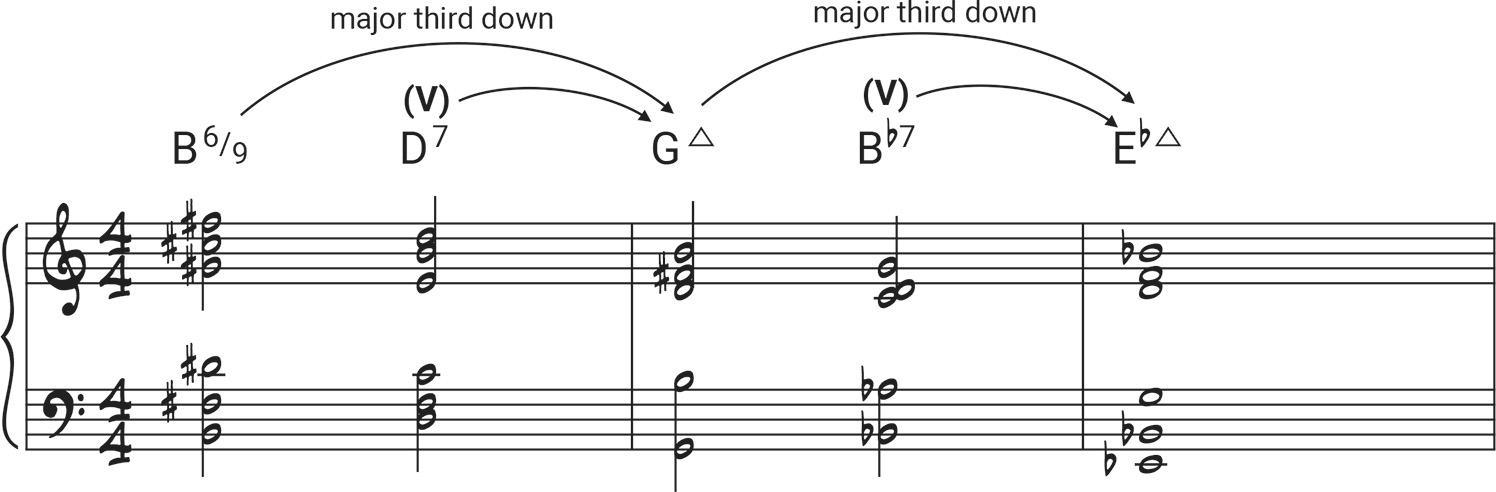

Coltrane changes come in many shapes and forms, but have at their core modulations in major thirds. For example, his composition “Giant Steps” starts with the following progression:

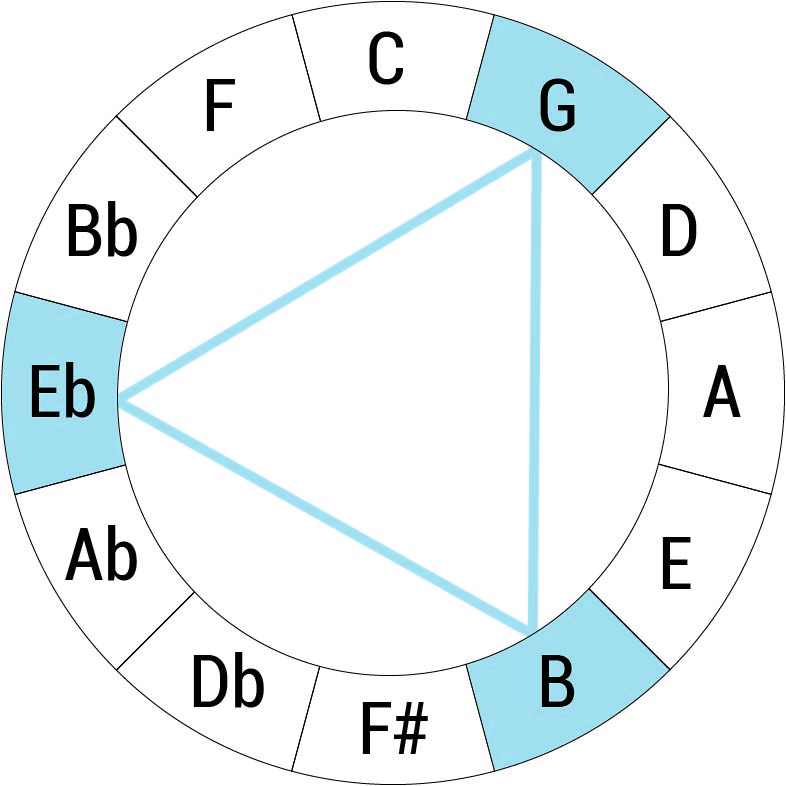

The three keys are: B major, G major (a major third down), and Eb major (another major third down). If you move down another major third, you get to where you started (B major). These chords are connected by secondary dominants, the V7 chord that leads to each of those chords: D7 to G, and Bb7 to Eb. If you look at the circle of fifths, the three tonalities (B major, G major, and Eb major) are connected by a triangle:

If you rotate this triad, you can find different combinations of tonalities, a major third apart. For example, if we turn the dial to D, we’ll get D, F#, and Eb:

Turnaround

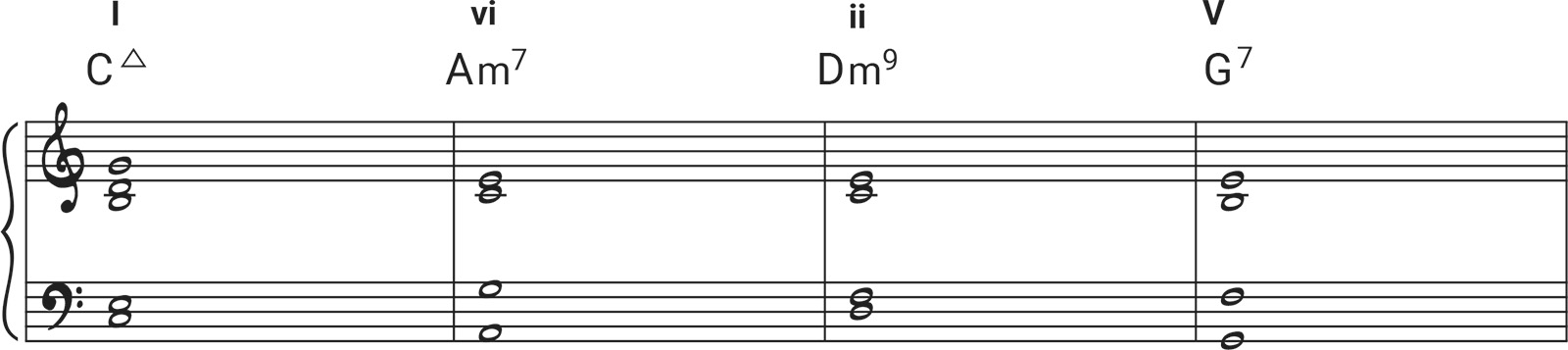

Let’s see how we can use these chords to dress up a turnaround. A turnaround is a progression of chords, usually at the end of the tune, which brings you back to the top of the form. A basic turnaround in C major looks like this:

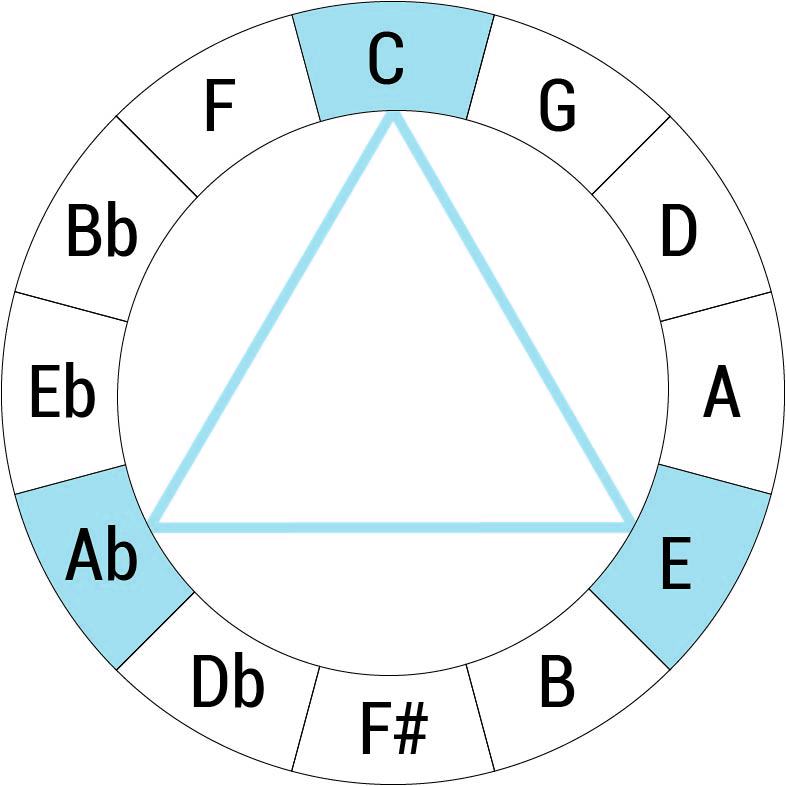

Next, let’s turn the triangle to C major:

The chords we get are:

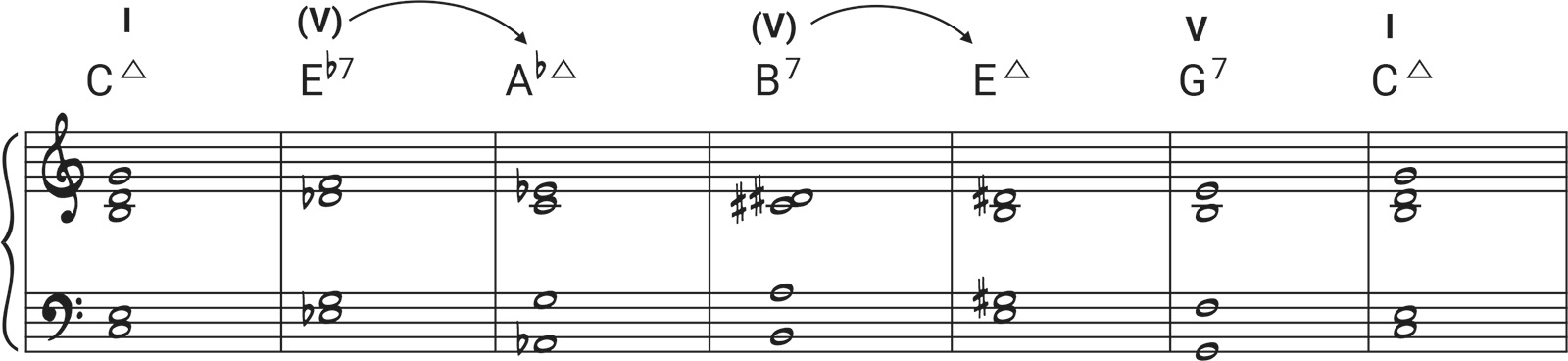

Now we’ll add a secondary dominant before each chord:

And there you have it, your Coltrane turnaround!

As you can see, we started with four chords in the original turnaround and ended up with six (before resolving to C major) on the final version. If you’re playing a song at a steady tempo, it’s hard to fit all those extra chords. But, as you saw in the example that I started with, when you’re playing solo piano, especially in a ballad, you can stretch the time and easily fit these chords in.

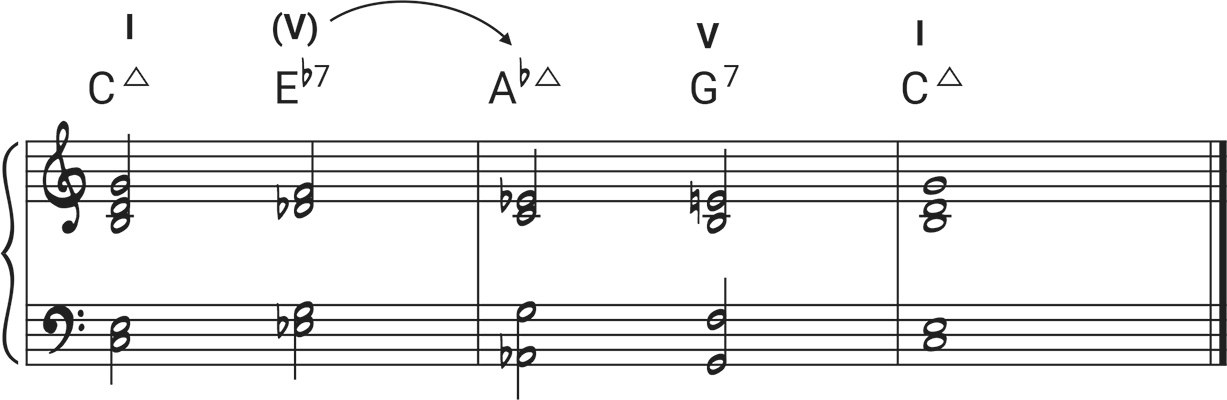

If you do play a song at a steady tempo, you can cut the turnaround short and resolve back to the tonic after Ab major. This way, you’ll stay in the 4-chord pattern:

Interestingly, this particular progression preceded Coltrane changes, as jazz composer Tadd Dameron used it in his 1939 composition “Lady Bird” — 20 years before Coltrane recorded Giant Steps!

Coltrane changes before Coltrane

Here’s another earlier example of a jazz composition that modulates in major thirds: In 1937, Richard Rodgers composed the song “Have You Met Miss Jones.” The bridge goes as follows:

As you can see, these chords modulate in major thirds, exactly like Coltrane changes do!

Conclusion

Coltrane changes can be a great tool to expand your harmonic horizon. I highly recommend practicing these examples in all keys. If you do, you’ll eventually be able to quickly use them while playing live, adding interest and variation to your piano accompaniments.

I hope you found this post useful. Let me know in the comments if you ever use these changes, and which versions. This post is not a complete list, as there are many more Coltrane compositions and ways of playing Coltrane changes.

As always, make sure to grab my free Reharmonization Quick Guide to get started on your own reharmonizations in five easy steps: get your copy here.