Two years ago, I was given a challenge.

Write a film score that starts as 70s neo-noir (think Taxi Driver) and gradually turns into a classic 1940s film noir in black and white (think Double Indemnity). In other words, could I compose a score that travels backwards in time, just like the film?

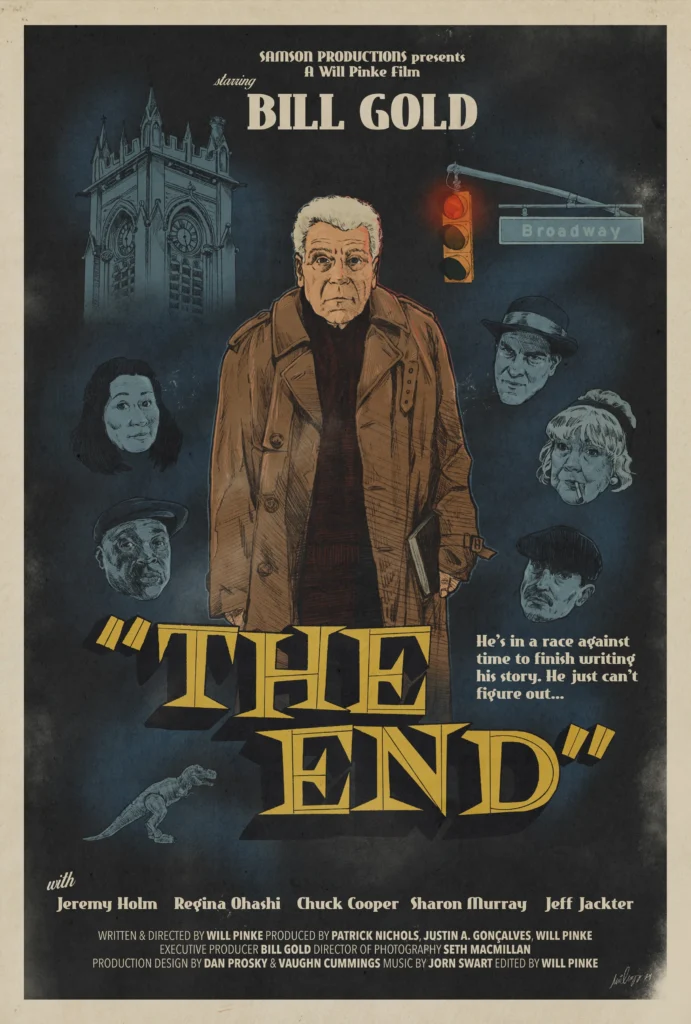

That challenge became the score for The End, a short film directed by Will Pinke, which recently premiered on Omeleto. You can watch it at the bottom of this post or follow this link.

In this blog post, I’ll share how I tackled writing this score, and a few things I learned along the way.

The film

The story features Sam, an aging, wannabe mystery writer struggling to finish his first detective novel. Over the course of one eventful evening, the lines between his real and fictional lives begin to blur.

Musically, the film begins in 70s neo-noir territory, drawing on the jazz-inspired scores of films like Taxi Driver, The Long Goodbye, and Chinatown. Think smoky saxophone, a small jazz ensemble, and a more intimate, psychological atmosphere.

As the film unfolds, both the visuals and the music gradually move backwards in time, transitioning into the lush symphonic textures of classic 1940s film noir. Think Double Indemnity, The Big Sleep, or The Maltese Falcon.

So not only did I have to write true to a specific genre, but I also had to move between two different eras smoothly. This was a challenge, but I’m always up for one!

Here’s how I tackled writing this particular score.

Step 1: Study the Genre

The first thing I did was completely immerse myself in the genre I was about to write in. I watched more than a dozen movies for this purpose. This was so much fun. There’s something about watching a movie while paying attention to the score that completely changes the way you experience it. You start noticing the different ways music can affect what you’re seeing. At times, it can tell you something the characters don’t know yet. Sometimes the score clashes with what you’re seeing, which creates a feeling of unease. It was also interesting to observe where the music starts and cuts out again, and what effect that has on the scene.

Motifs / leitmotifs

Watching these movies, I started paying close attention to the themes, or “motifs”, the short melodic phrases that make up the score. When such a phrase is attached to a specific character, location, or idea, it’s often called a leitmotif. These are extremely prominent in classic film noir.

For example, in The Big Sleep (1946), with score by Max Steiner, the most frequently used motif is Marlowe’s Theme. This motif appears 59(!) times throughout the film. (Source: https://maxsteinerinstitute.org/)

At 0:59, you can hear the theme when Marlowe introduces himself jokingly as “Doghouse Riley” (for the record, it’s not a joke I understand):

Classic film noir versus neo-noir

Film scores in classic film noir from the 40s and 50s are characterized by a full orchestra, lush symphonic sounds, chromatic harmonies, heavy use of leitmotifs, and a tense romanticism. The music often tells you what to feel and makes bold emotional statements.

A classic film noir sound:

Neo-noir has a more modern, jazz-driven sound. You often hear trumpet or saxophone, creating a smoky, urban atmosphere. Instead of a large orchestra, the ensemble is smaller, sometimes closer to a jazz band.

There is less heavy use of leitmotifs and less scoring of every little action on screen. The music captures an internal psychological struggle of the protagonist, a feeling of isolation rather than grand tragedy. It feels like it’s coming from inside the character, rather than commenting from above on what’s happening.

For example, here’s the main title from Taxi Driver (saxophone theme enters at 0:57):

Step 2: Spotting session

One of the most important steps in writing a film score is the so-called spotting session. This is when you sit down with the director, watch the movie, and together identify all the moments where score might be needed. You can discuss tone, mood, ideas for instrumentation, and specific musical purposes. For example, this was one of the notes I took for the moment in the film at 3:38:

Cue 6. Wandering 1 starting at the fade from diner

Dips down as we fade into focus, the ringing happens, then we fade in again.

Surrealism starts to reveal itself. Add in weirder thing, at the phone booth. Discovery theme. Flute / vibraphone, something off. Jazzy but add new element. The thing that reminds him that he’s somewhere else. “The good the bad and ugly” motif. A sound whistling to him: wake up, but he doesn’t wanna hear it.

(Side note: clock ticking?)

Step 3: Composing themes

Now the real thing starts: writing themes! I start with the Main Theme, as this is what sets the tone for the entire score.

Before getting into the actual theme I wrote, here are three elements that I think are essential when writing film noir music.

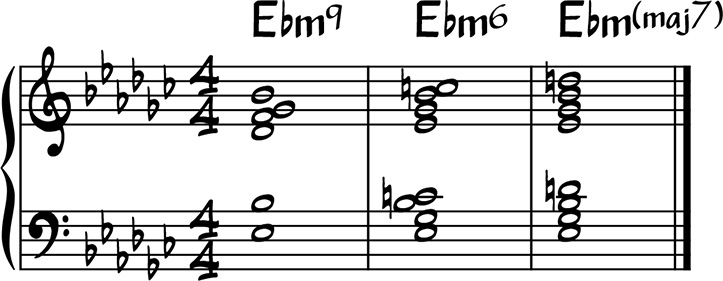

1. Minor 7, Minor 6, and Minor(maj7) chords

If you want that classic film noir color, chords like minor 7 (especially with a 9), minor 6, and minor(maj7) are great places to start. They immediately create that uneasy, mysterious, slightly brooding feeling. Even before writing a melody, just sitting on those sonorities already sets the mood:

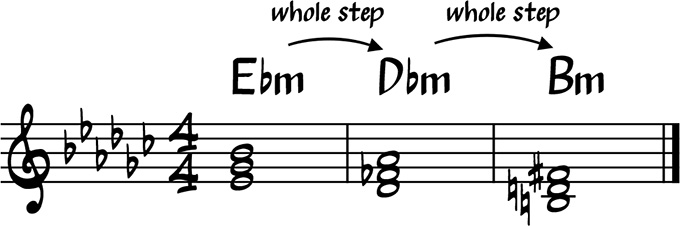

2. Chromatic or Parallel Harmonic Movement

Moving minor chords chromatically, for example by half-step, or in parallel motion, is a great way to increase the dramatic character that’s so prominent in classic film scores. It has an almost Wagnerian character and creates an instant noir feeling.

3. Chromatic Melodies

Film noir melodies often move chromatically or outline altered tones within the harmony. Even a simple stepwise chromatic line can sound mysterious when placed over these types of chords.

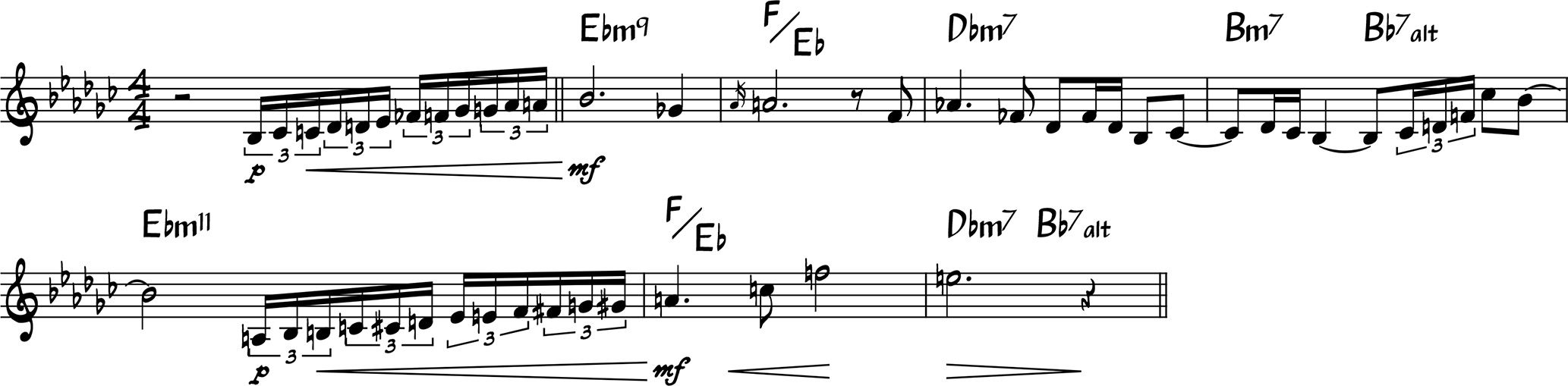

I used a chromatically falling melody (from Bb to A, to Ab) and added some additional chords to connect the minor chords with eachother. That became this jazzy saxophone theme (played by my fellow Malnoia member Lucas Pino), rooted in the neo-noir sound:

Main Theme “Harry Powers Theme” (used throughout the film)

This motif, the descending bluesy melody, comes back a dozen times throughout the film, in different instrumentation, moods, and keys. I think of it as Harry Powers’ motif, Sam’s imaginary character, functioning as a through-line in the story. Using the theme throughout the film helps tie everything together and makes the score feel cohesive.

Working from my notes from the spotting session, I then created the other themes and motifs:

Discovery Motif (3:56, 6:49)

The sound that signals strangeness, surprise, a dreamstate:

Bogard Motif (4:12, 14:09)

A not-so-subtle nod to one of the greatest actors in noir, who makes a cameo of sorts in this short film

Danger Motif (9:48, 10:26, 11:33)

This one doesn’t require further explanation:

Waitress Motif (0:48, 13:32)

This one is quite subtle. I’m not sure it really functions as a leitmotif, but it ended working well, even as “regular” score:

You can have a lot of fun with this. Creating small melodic characters and moods, letting them return, weaving them into different scenes, connecting them through harmony, even layering one motif on top of another. That’s what makes a composition start to sound like a film score. It follows what’s happening on screen, but it also gives the story a musical identity.

Step 4: Orchestrating

As I mentioned, the challenging thing of this movie was that it started out in the jazzy Neo-noir genre, but slowly evolved into traditional noir. This meant that both the composition and orchestration needed to evolve. I did this by slowly introducing strings, and while I started with saxophone (played beautifully by my fellow Malnoia member Lucas Pino), I had him switch to clarinet and bass clarinet as the movie went on, to be more in line with a classical sound.

At the end, the main theme we first heard in the diner returns, this time with a full orchestral texture.

You can hear the Main Theme above, and then compare it to the closing theme:

Step 5: Production and recording

I think it’s really important, even on smaller productions and budgets, to try to record as much of your score live as possible. It adds so much character and makes the score feel, quite literally, alive. You can be creative with what you have. If you’ve got a good mic, you can record almost anything. Then you can blend it with software instruments if needed, as long as there are some live elements in the mix.

During the composition process, everything was “in the box”, created inside my software using only MIDI instruments. After the full score was approved, it was time to record the real instruments. I recorded my upright Yamaha U3 for the piano parts. Lucas Pino recorded the saxophone and woodwinds, with additional parts by Evan Harris. Rodrigo Recabarren played drums and percussion, and Benni von Gutzeit, the other Malnoia member, recorded the string parts.

Of course, I didn’t have access to a full symphonic orchestra. To create that larger sound, I layered orchestral plugins from Spitfire Strings with Benni’s live recordings. The live strings bring realism and breath, while the plugins provide size and depth.

The film

Below is the final result.

Film scoring is a wonderful process, and I learned a lot doing this. I’m happy with how this score turned out, and I certainly hope to do many more!

I hope you enjoy this breakdown, and the film, of course! Feel free to share it with friends or anyone you think might like it. And please share any thoughts or comments in the section below.

And if you enjoy thinking about harmony and color in this way, make sure to download my free Reharmonization Quick Guide!